I originally planned to write this article right after publishing the previous one, but as always, life had other plans. Nevertheless, it's time to dive back into the latest trends shaping computer science research.

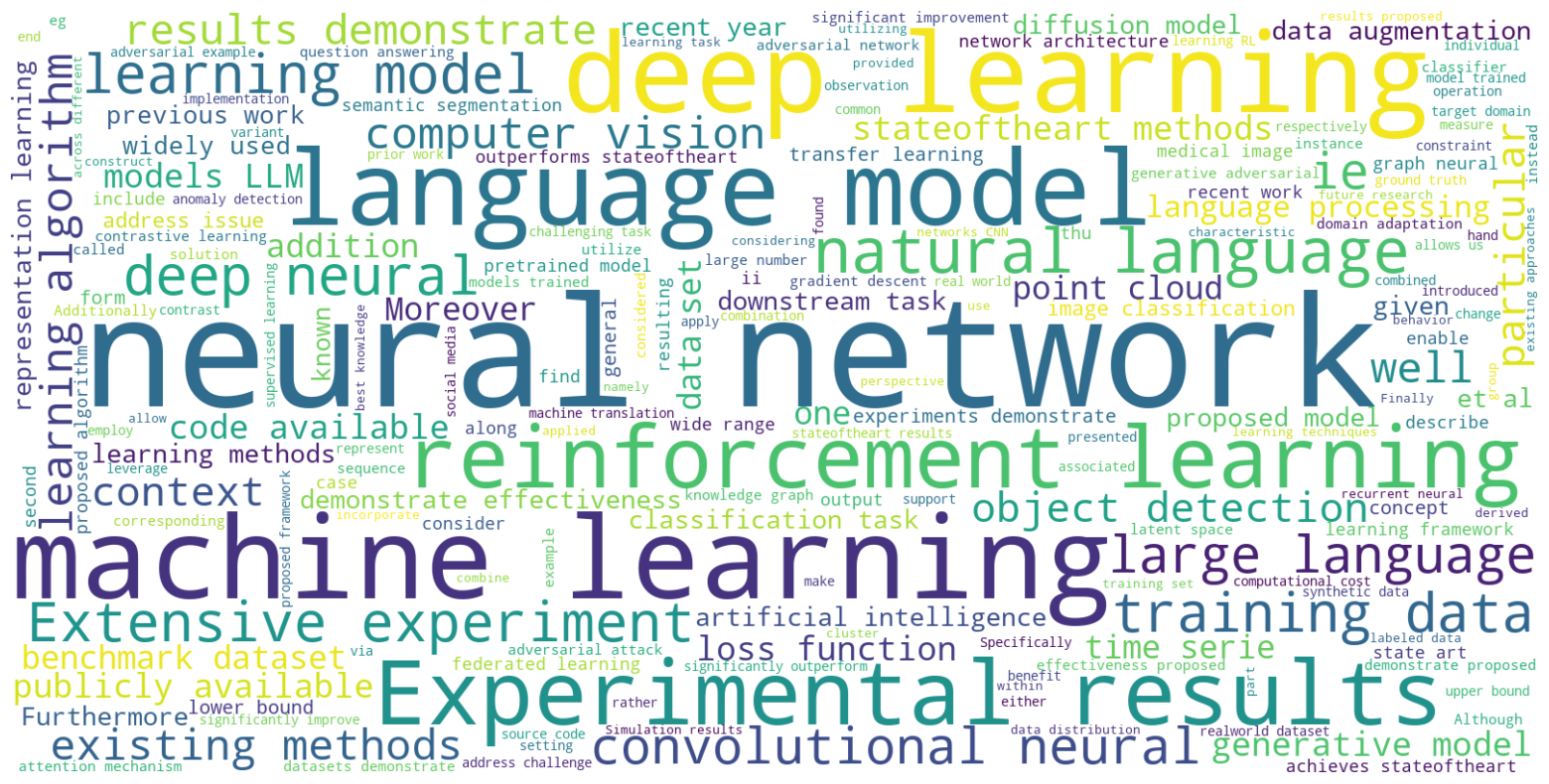

The word cloud in the banner image—and introduced in the previous article—highlights the most common terms extracted from arXiv papers. Below, you’ll find the full list of extracted words. If you're interested in exploring the complete dataset, simply click ‘All Words’ to expand it:

All words

All words extracted using the wordcloud Python package from papers published since 2007:

neural network, language model, machine learning, deep learning, Experimental results, large language, reinforcement learning, Extensive experiment, natural language, learning model, training data, deep neural, models LLM, convolutional neural, ie, existing methods, results demonstrate, computer vision, code available, learning algorithm, diffusion model, publicly available, generative model, stateoftheart methods, object detection, loss function, time serie, well, point cloud, particular, artificial intelligence, benchmark dataset, addition, context, language processing, demonstrate effectiveness, data set, Moreover, address issue, experiments demonstrate, downstream task, recent year, learning methods, classification task, representation learning, data augmentation, widely used, proposed model, previous work, et al, image classification, wide range, outperforms stateoftheart, one, transfer learning, federated learning, pretrained model, address challenge, given, semantic segmentation, known, Furthermore, form, lower bound, achieves stateoftheart, learning framework, medical image, include, network architecture, graph neural, datasets demonstrate, ii, state art, concept, resulting, significant improvement, consider, output, question answering, describe, contrastive learning, along, latent space, adversarial attack, knowledge graph, effectiveness proposed, second, recent work, models trained, attention mechanism, proposed algorithm, general, significantly outperform, find, significantly improve, demonstrate proposed, computational cost, thu, large number, domain adaptation, gradient descent, across different, source code, anomaly detection, Additionally, ground truth, across various, generative adversarial, synthetic data, combined, utilize, proposed framework, future research, corresponding, case, instance, adversarial network, considered, prior work, enable, employ, Although, upper bound, contrast, combination, variant, learning RL, realworld dataset, model trained, make, called, social media, target domain, operation, machine translation, stateoftheart results, real world, instead, benefit, apply, challenging task, allows us, example, existing approaches, classifier, eg, data distribution, realworld application, labeled data, learning techniques, adversarial example, observation, foundation model, utilizing, outperforms existing, supervised learning, rather, end, implementation, autonomous driving, introduced, represent, sequence, measure, either, recent advance, change, training set, leverage, cluster, feature extraction, compared stateoftheart, provided, perspective, networks CNN, hand, computational complexity, learning task, best knowledge, associated, found, results proposed, allow, characteristic, considering, incorporate, behavior, support, recurrent neural, individual, commonly used, image segmentation, namely, Simulation results, respectively, call, part, construct, common, presented

We'll go over the most relevant terms, filtering out common or redundant words. As Albert Einstein famously said:

If you can't explain something in simple words, you don't understand it well enough

Ignored Words

These words are excluded from our analysis as they are either too common or redundant:

Extensive experiment, learning model, deep neural, models LLM, ie, existing methods, results demonstrate, code available, well, particular, addition, context, language processing, demonstrate effectiveness, Moreover, address issue, experiments demonstrate, downstream task, recent year, learning methods, widely used, proposed model, previous work, et al, image classification, wide range, outperforms stateoftheart, one, address challenge, given, known, Furthermore, form, achieves stateoftheart, learning framework, include, datasets demonstrate, ii, state art, concept, resulting, significant improvement, consider, output, describe, along, effectiveness proposed, second, recent work, proposed algorithm, general, significantly outperform, find, significantly improve, demonstrate proposed, thu, large number, across different, source code, Additionally, across various, combined, utilize, proposed framework, future research, corresponding, case, instance, considered, prior work, enable, employ, Although, upper bound, contrast, combination, variant, model trained, make, called, operation, stateoftheart results, real world, instead, benefit, apply, challenging task, allows us, example, existing approaches, eg, realworld application, learning techniques, adversarial example, observation, utilizing, outperforms existing, rather, end, implementation, introduced, represent, sequence, measure, either, recent advance, change, training set, leverage, compared stateoftheart, provided, perspective, networks CNN, hand, computational complexity, learning task, best knowledge, associated, found, results proposed, allow, characteristic, considering, incorporate, behavior, support, individual, commonly used, namely, Simulation results, respectively, call, part, construct, common, presented, publicly available, models trained, medical image, lower bound, learning rl, social media

Brief Explanations

Now, let’s explore the key terms extracted from nearly two decades of computer science research. I’ll arrange them in a logical order so that one concept naturally leads to the next.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a branch of computer science dedicated to creating machine-based systems that can perceive, reason, plan, learn, and make decisions—much like humans do. Broadly, any automated system can be viewed as a form of intelligence, with varying levels of complexity and problem-solving abilities. At the most advanced end lies Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—a machine capable of tackling any task or problem it encounters. Pursuing AGI is a major goal for governments, corporations, and research institutions alike, as it promises a versatile solution to virtually every conceivable challenge.

Machine Learning

When trying to build Artificial Intelligence (AI), there are generally two ways to give machines “intelligence”:

- Hand-coded Rules: Write down every single rule or step the machine should follow. For example, you could program a chess computer by teaching it every valid chess move and telling it exactly what to do in each situation. This is time-consuming, but precise. It often relies on logic and principles which we can

- Learning from Data: Provide the machine with lots of examples and let it find patterns on its own, without explicitly programming every rule.

The second approach is known as Machine Learning (ML). In ML, a computer uses a learning algorithm to discover patterns in large amounts of data—rather than relying on rules that programmers have written by hand. This ability to “learn” from data makes ML the most popular way to build modern AI systems. The output of a learning algorithm is a trained machine learning model, often referred to as an ML model.

Types of Learning

When we talk about a machine learning from data, we're essentially deciding how it acquires knowledge. Just as humans learn from parents and teachers telling us what's right or wrong, by interacting with different objects around us, or by introspecting—so too can a machine. These approaches are commonly grouped into three main categories (though the third, sadly, didn’t show up among the most common words from the research, it remains one of the most important). Understanding these categories helps us appreciate why certain algorithms excel at specific tasks and how different learning methods can be combined to build more versatile AI systems.

-

In Supervised Learning, the machine is trained on a labeled dataset—meaning each example comes with the “correct answer.” This correct answer is often referred to as the ground truth. Think of it as having a personal tutor who checks your homework: you try to solve math problems (predict something), and the tutor immediately tells you if you’re right or wrong. Over time, you learn to get more problems right on your own. This is the most common way of training machines.

-

With Reinforcement Learning (RL), machines learn by trial and error in an environment that rewards or penalizes their actions. This is somewhat like training a pet: when the pet does something good (e.g., fetch a ball), it gets a treat. When it messes up (e.g., chew on your slippers, poop on your sofa), it gets scolded. Over many attempts, the dog and the same with a machine, figures out which actions yield the best outcomes in different scenarios.

-

In Unsupervised Learning, there are no labeled examples—no right or wrong answers. The machine’s job is to uncover hidden patterns or structures in the data. Unsupervised methods are especially valuable when labels are scarce or non-existent, and they often serve as a foundation for more advanced tasks in both supervised and reinforcement settings. This is the most common way humans learn, finding patterns in everyday observations and self-discovery.

Datasets

A dataset is simply a collection of examples used for machine learning. Depending on the learning approach, these examples may be labeled, partially labeled, or entirely unlabeled. The size of a dataset can range from just a handful of examples—often referred to as a few-shot learning scenario, where models strive to learn effectively with minimal data—to billions or even trillions of examples.

The dataset used to train a model is called the training dataset. In a typical machine learning project, many design choices—such as the learning algorithm or pace of learning—must be made. A validation dataset helps in making these decisions by helping us tweak these levers. Finally, a test dataset is used to assess how well the model performs on previously unseen data. Together, these three sets are often referred to as a benchmark dataset, providing a consistent basis for comparing different learning algorithms.

Data Distribution

In a dataset, to describe where the data comes from, which domain, the range in which it lies, and the variability we can expect in the data, we call it data distribution. If a data point does not fit within the dataset’s usual range, it is said to be out-of-distribution or out-of-domain. And, the domain you collected the data for is called the target-domain. One of the more prized capabilities of a machine learning algorithm is to handle such out-of-distribution data effectively—a challenge often tackled by domain adaptation. This is also known as out-of-distribution generalization.

Real-world data frequently comes from sensors such as satellites, cameras, traffic lights, or everyday devices like smartphones. Additional data can also be created through a technique called data augmentation—for example, rotating an image of a cat still yields a valid example for training a cat-recognition model. Data can be generated in many other ways as well, such as creating various valid shuffles of poker-cards combinations to build a dataset of poker. Both data augmentation and generating data that isn’t directly observed are forms of synthetic data, which is heavily used in machine learning.

Tasks in Machine Learning

Until Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) becomes widely available—if it ever does—we need machines capable of performing specific tasks. Even if AGI eventually exists and remains accessible only to a small group of people (due to massive computational requirements), purpose-built models will still be essential. After all, physical constraints like size, energy consumption, and raw materials make it impractical to deploy a single universal intelligence everywhere (yet).

"You don't need a bulldozer to trim a small garden of flowers and bushes." - me

As we were talking about datasets, domain, etc.; Tasks in Machine Learning are defined based on what data we can collect, store, move-around in computers, wherein the artificial intelligence resides. In a computer, we can collect data formats like text, images, audio, videos (they are just images and audio aligned on the time-scale). The tasks in Machine Learning thus revolve around manipulating or identifying these discrete formats, most machine learning tasks fall into a few broad categories sharing common solutions, techniques and underlying principles. Irrespective of the format of data, most use cases boil down to two main objectives:

- Tell or take action based on data, which are known as discriminative tasks.

- Generate new information from what you already know, which are known as generative tasks.

There are many names of different niche problems in machine learning. Classification assigns labels to inputs—such as detecting spam emails or deciding if an image contains a cat or a dog—while anomaly detection focuses on spotting unusual patterns (e.g., fraudulent transactions). Object detection localizes and identifies objects in images by drawing bounding boxes around them. In image segmentation, an image is partitioned into meaningful regions by grouping similar pixels, whereas semantic segmentation goes even further by classifying each pixel into a specific category (like distinguishing cars from pedestrians). These methods form the backbone of applications like autonomous driving, surveillance, and medical imaging, where fine-grained visual understanding is critical. On the linguistic side, machine translation converts text from one language to another or answer a given question. This capability drives cross-lingual communication and global collaboration, making it a cornerstone of many modern AI systems.

Across all these tasks, researchers continually push the boundaries with new state-of-the-art approaches, which set fresh benchmarks for accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability in real-world scenarios. Whether it’s classifying images, detecting anomalies, or translating text across languages, these specialized (and increasingly powerful) models illustrate how far we’ve come—and how much potential remains—in the evolving field of machine learning.

Neural Networks

Neural networks is basically a network of neurons. Neurons in computers are modeled against the neurons in our brain. They are tiny decision makers.

- Computer Neuron: A neuron takes a handful of numbers (inputs), multiplies each by a personal “preference” (weight), adds a bias term (its gut feeling), then asks a nonlinear question like “Is the result bigger than zero?” The answer—usually squashed between 0 and 1—gets passed along.

- Neural Network: Connecting tens, thousands, ..., billions of computer neurons to create a neural network. The architecture of the neural network defines how these neurons are connected to each other and how the information flows between them, kind of like wiring of these neurons.

During training, gradient descent nudges each weight so the neuron’s output helps reduce the overall loss function. Think of millions of microscopic knobs twisting in concert until the network’s predictions finally land on target. One neuron might detect an edge in an image, a pop in an audio clip, or the word “not” in a sentence. Stack thousands into layers, and higher-level concepts emerge—eyes, chords, sarcasm. It’s emergent complexity built from embarrassingly simple parts.

Real brain neurons fire spikes; artificial ones shuffle floating-point numbers. The metaphor isn’t perfect, but the inspiration holds: lots of tiny units, each with limited insight, can collaborate to form rich perceptions and decisions.

Representing Data For Learning

Before any model can dazzle us with predictions, it first has to see the data in a way that makes sense. That early makeover stage—turning raw pixels, characters, or sensor blips into something a machine can reason about—is called feature extraction.

-

Hand-crafted features (the classics). Once upon a time, engineers manually designed edge detectors for images or TF-IDF vectors for text. These features worked, but they were brittle and labor-intensive—you needed domain expertise for every new problem.

-

Deep learning takes over. Modern neural networks learn their own features directly from data. Layer by layer, they transform inputs into increasingly abstract patterns. Early layers might notice edges or phonemes; deeper layers latch onto faces, topics, or heartbeat irregularities. This automatic discovery process is what we call representation learning.

-

Contrastive learning: teaching by comparison. Suppose you have two different photos of the same dog. A contrastive learner pulls those images together in its latent space while pushing random cats, cars, and cupcakes apart. With no labels required, the network learns a rich encoding that often rivals fully supervised training. Techniques like SimCLR, MoCo, and CLIP ride on this idea.

-

Why “latent space” matters. Think of latent space as a high-dimensional map where similar things cluster naturally—dog images here, jazz riffs there, fraudulent transactions way over there. A well-shaped latent space makes downstream tasks (classification, retrieval, even generation) dramatically easier and hopefully reducing the dimensions to allow for information compression.

-

The gritty details: gradient descent & loss functions. All this learning happens because the network repeatedly guesses, measures error via a loss function, and nudges its weights using gradient descent. Whether you’re minimizing contrastive loss or cross-entropy, the same feedback loop keeps sculpting better features.

Feature extraction has evolved from painstaking manual craft to self-taught artistry. The result: models that not only work better but also adapt faster to the next big dataset we throw at them.

Most Common Architectures

Once you’ve coaxed useful features out of the data, you still need a scaffold to process them. Enter the architecture—the wiring diagram that decides how information flows, mixes, and re-emerges as predictions. Some of the most popular architecture are:

-

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) Text, sensor logs, and other time-series streams need context from previous steps. RNNs recycle a hidden state forward in time, giving them short-term memory. Variants like LSTM and GRU fight “forgetfulness,” though they’re mostly outpaced by transformers.

-

Transformer + Attention The engine behind large language models and, increasingly, vision and multimodal systems. Self-attention lets every token (or patch or features) look at every other (at least theoretically as many variants reduce computational burden by caching, MOE), capturing long-range dependencies without the memory glitches that plagued old RNNs. These are often able to work with natural language, i.e., the language of humans.

-

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) A convolutional layer slides a small set of neurons formed like a tile over an image (or audio spectrogram) the way you’d move a magnifying glass across a map. Because those neurons are shared across positions, CNNs recognize a cat whether it’s in the corner or the center—perfect for vision, speech, and video tasks.

-

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) For data that’s more “who’s connected to whom” than pixels on a grid—think knowledge graphs, molecules, or social webs. Relation-aware variants ensure “friend-of” isn’t mistaken for “capital-of.”

-

Point-Cloud Networks: 3-D dots, no pixels required. Lidar scanners spit out unordered XYZ points. PointNet, PointNet++ and their descendants process these clouds directly, making them the eyes of autonomous driving (a car driving the computer), robotics, and AR/VR mapping systems.

Each neural network architecture can be seen as a stack of layers of neurons. Wider and more layers of these lego blocks of architectures give you richer representation—but also bigger computational cost. Engineers constantly have to think about FLOPs (floating-point operations), memory footprint, and inference latency the way architects have to think about budget, space, and structural load.

Today, most of these architectures (especially transformer models) debut as massive foundation models—giant pre-trained networks that have already learned broad skills from mountains of public data. With transfer learning, you simply nudge that big model on your small, task-specific dataset instead of starting from scratch. And when privacy keeps data on devices, federated learning lets each phone or hospital train its own copy locally, share only tiny weight updates, and still help build a smarter global model.

Generative Tasks

- Generative models do the opposite of classifiers: instead of labeling what is, they imagine what could be. Feed one enough cat photos and it will invent convincing new felines from thin air.

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) sharpen that skill by pitting two nets against each other—the “artist” tries to fake data, the “critic” tries to spot fakes. This back-and-forth forms the classic adversarial network setup and has given us photoreal faces, deep-fake videos, and endless meme templates.

- Diffusion models take a different path: they add noise to real data until it’s pure static, then learn to run the movie in reverse. Step-by-step denoising yields images and videos so crisp they now headline most generative benchmarks.

- The dark twin of all this creation is the adversarial attack—tiny, often invisible tweaks that make a stop-sign look like a speed-limit sign to an autonomous car. The same insights that teach a model to dream can also teach it to hallucinate in dangerous ways.

Closing thoughts

I’m posting these reflections a little later than planned—2025 trends are already knocking—but curiosity doesn’t run on a calendar. If today’s dive sparked even one new question in your mind, mission accomplished. Thanks for tagging along, and stay tuned: the next surge of breakthroughs is already warming up in the arXiv queue, and I’ll be back to unpack it with you. Until then, keep tinkering and keep asking “what if?”—that’s how the future gets built.